Celebrating Wonder Drugs

It’s hard to imagine what life was like before modern medicine. A world where a scratch could be fatal, there was no such thing as routine surgery, and many childhood diseases had poor outcomes seems so foreign to us. We often take life for granted in the 21st century but let’s turn the calendars back several decades and reacquaint ourselves with a couple of medical marvels that changed everything. Let’s start here in Canada.

Diabetes is a disease that no one ever wishes for but for children, Type I or juvenile diabetes was a nightmare. Because of the inability of the body to deal with sugars, patients were put on extremely low carbohydrate diets. Children barely survived as these diets left them malnourished but the lack of sugar in their food managed to keep them alive…just barely. Poor quality of life and an even poorer prognosis left diabetes a disease to be feared. And then, a few Canadians came along.

Dr. Frederick Banting had an idea. Working with colleagues Charles Best (research assistant), James Collip (biochemist), and John Macleod (physiology) at the Toronto General Hospital, he realized that patients who couldn’t produce their own insulin could be supplemented with the hormone. Insulin, created in the pancreas, helps regulate carbohydrates in the body. However, it’s this key hormone that’s missing in those with type I diabetes. Banting’s hunch was put to the test in 1922 on a 13-year-old boy who by point had withered away to little more than a skeleton. After a bit of tweaking on the formula, diabetes was no longer a death sentence.

This stamp was issued on April 15, 2021 to commemorate the 100th anniversary of this miracle that has saved countless lives and was the beginning of understanding this disease that will one day – hopefully – have a cure.

Penicillin. I don’t even know how to start this paragraph because that one word – penicillin – is full of so much meaning. In fact, that little drug is probably the reason why so many of us are still alive. Yet, so many people have no idea what life was like before the antibiotic age. We’re going to find out about it soon though because of our overuse of these drugs.

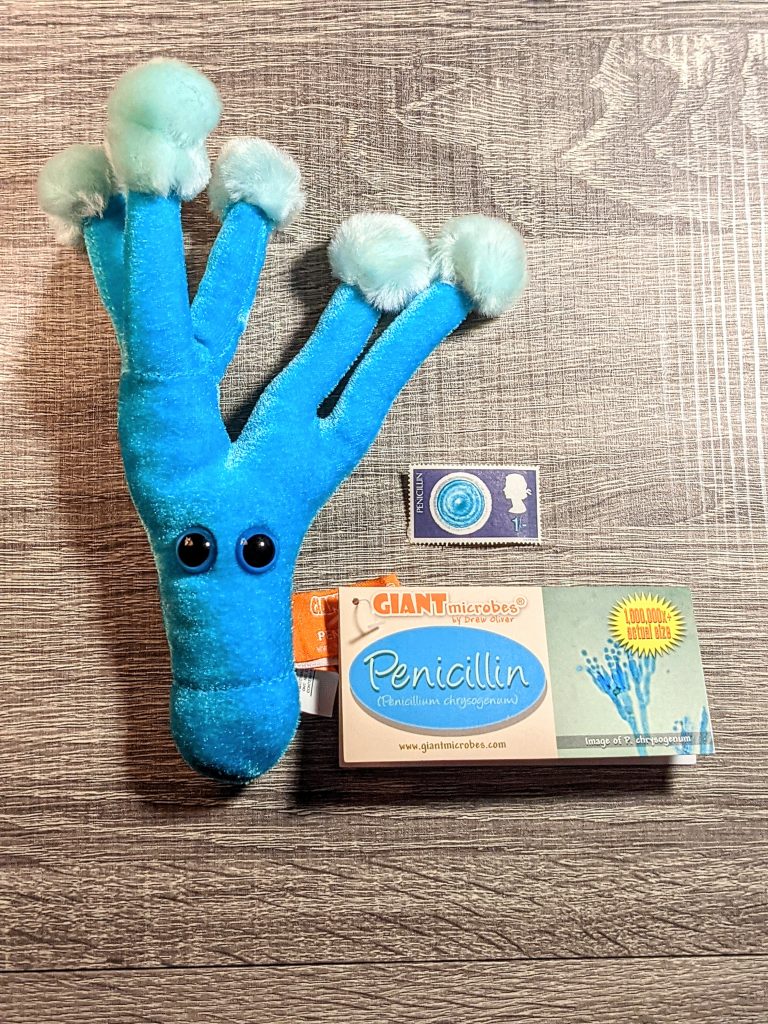

Okay, let’s start with the stamp itself. Released in Great Britain in 1967, this stamp was a part of a series celebrating British discoveries including radar, television, and the jet engine. It features a lovely blob of penicillium fungi next to the iconic profile of Queen Elizabeth which is the defining feature of a British stamp.

I’m sure you’ve probably heard the story before. Alexander Fleming, working at St Mary’s Hospital in London way back in the day was working on an experiment that got contaminated. He tossed his petri dishes aside and forgot about them until much later and then – badda bing, badda boom – he discovered penicillin. Not exactly but it would be nice if history was that simple!

In 1928, Flemming was indeed working on an experiment. In fact, he was working on the influenza virus which had just devastated the world 10 years earlier. As the real story goes, he took off for a two-week vacation, and upon returning to the lab, he noticed that a plate of staphylococcus bacteria was contaminated with mold. As a former lab technician myself, I can tell you that there’s nothing more disappointing than finding mold on your plates, and those petri dishes get promptly tossed in the biohazard bag to be autoclaved later. But Flemming noticed something interesting. Instead of the mold simply growing on top of the staphylococcus colonies the fuzzy blob cleared a ring of bacteria indicating that it was releasing something that killed bacteria.

Flemming continued to work with the Penicillium mold until 1931 when the project was passed on to Howard Florey and Ernst Chain, at Oxford University. Why? I’m not sure but it was these two who developed the medicine we all know as penicillin.

Antibiotics like penicillin are vitally important to life as we know it. Surgeries are now possible because the threat of bacterial infection is (mostly) eliminated. Even a small cut can be (almost) guaranteed to not get infected because, in addition to understanding the need for cleaning a wound, we have a number of topical antibiotic creams at our fingers. But unsurprisingly, we humans took a brilliant discovery and overdid it. Antibiotics have become so overused that bacteria have figured out how to avoid being killed by them. And while we have found a variety of different antibiotics that have different ways of killing bacterial cells, they too have figured out how to beat our new drugs. Now, we have nothing new. No new discoveries so when all the species of bacteria out there evolve enough to evade our last antibiotics, we’ll be back to square one.

I wish I had a happier ending for this post but alas, the only thing I can say is that if you like my little plush penicillium in these photos, go check out giantmicrobes.com. While I may not work in a lab anymore, my giant microbe collection always puts a smile on my face!